Part 1 - Were Shudras/Dalits Denied Education in the Pre-British Era?

Debunking the Myth that Shudras were kept away from education for 5000 years

It is a commonly held belief that before the British colonial rule, the Indian indigenous education system was rudimentary, religious in nature, and mostly restricted to the so-called privileged upper castes, especially Brahmins. It is also claimed, especially by left-leaning academicians/social activists, that historically Brahmins monopolized all the educational resources and denied education to the so-called lower castes (Shudra and Dalit castes).

However, the historical records from the 18th and 19th centuries reveal a different picture. The data available from various British reports (official as well as unofficial), not only shows an advanced indigenous Indian education system but also emphatically debunks the myth that Shudras/Dalits were denied indigenous education in the pre-British era.

Indian Indigenous Education Before British Colonial Rule

At the beginning of the 18th century, there was a lot of interest in India and Southeast Asia, amongst European scholars and travelers. Their interest mostly lay in the field of politics, laws, philosophies, and sciences, especially Indian astronomy. However, written descriptions of the education system were far and few. Scattered descriptions from various researchers and scholars reveal that in the pre-colonial era, education was valued greatly, both among Hindus and Muslims. Indigenous education was carried out through various pathshalas, madrassas, and gurukuls which were spread across every village/city of India. Imparting education was considered a religious duty. Almost every temple, mosque, and Dharamshala was attached to a school. These traditional educational institutions were maintained mostly via community contributions and included students from various castes, as well as religions, across India.[1] 1

However, a more detailed analysis of the indigenous education system was performed by the British during the early 19th century. To devise new policies for the induction of Western education and (Christian) religious values, the British government commissioned various surveys across India, which were conducted over 2 decades. By the mid-19th century, a considerable number of official and unofficial surveys on indigenous education had been carried out, in all 3 presidencies of British India (Bengal, Madras, and Bombay). [1,2]2

These reports not only revealed an impressive length and breadth of the existing indigenous education system but also showed a dominating presence of the so-called lower castes among the school population.

Following are the key surveys that provide detailed information on the nature of the Indian indigenous education system (including the curriculum, school population, and teaching methodologies) in the pre-British era:

1. Sir Thomas Munro Survey – Madras Presidency – 1822-26 [3,4,5]345

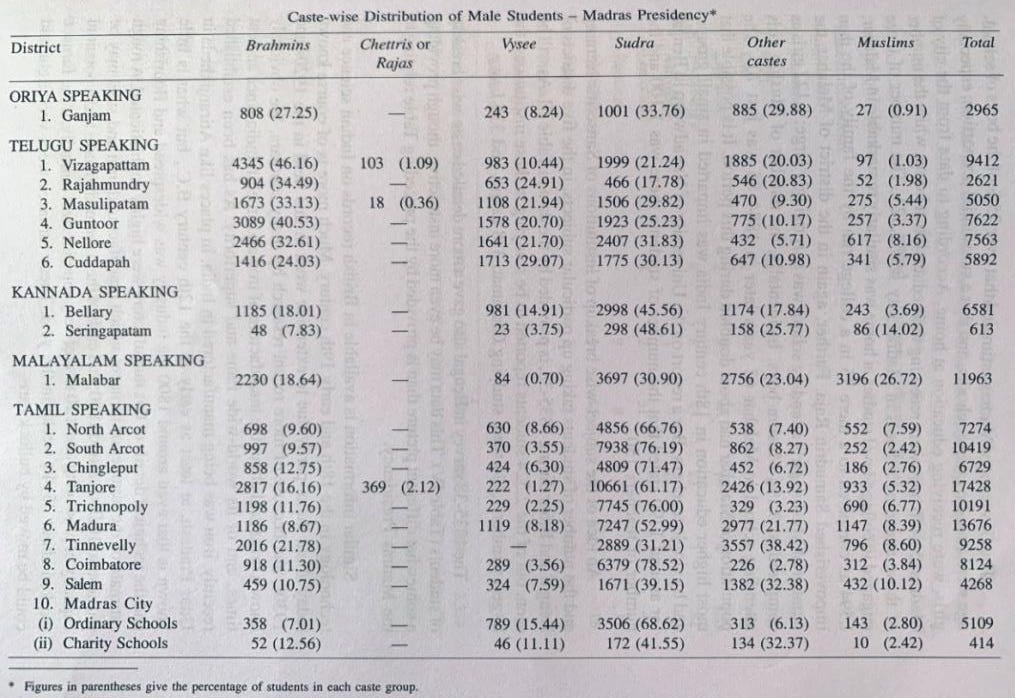

In June 1822, Sir Thomas Munro, the Governor of Madras, ordered an expansive survey across the districts of the Madras presidency. The district collectors were asked to furnish the caste-wise distribution of students in the existing indigenous schools. The students across districts were divided into 4 categories: Brahmins, Vaishyas, Shudras, and other castes (mostly the current-day scheduled castes, also referred to as "Dalit" castes).

Munro Statue in Chennai

Data from the survey (finally submitted in 1826) revealed that there was at least one school for every 1,000 people. Overall, there were 11,758 indigenous schools and 740 colleges (including 1,57,664 boys and 4,023 girls). Munro observed that elementary education was imparted to about 1/4th of the boys of school-going age. Also, many children (especially girls) were educated at home. Compared to the students educated at schools, four times more children were privately tutored at home.

The most interesting point was that the so-called Shudras and other castes (Dalits) predominated in these indigenous schools (almost 64%). On the other hand, the Brahmin scholars formed a very small proportion of those studying in schools (19%).

Caste-wise distribution of male students in schools (Madras Presidency) [Thomas Munro Report, 1826]

*Other castes included castes considered lower than Shudras [(earlier known as Panchamas (current day scheduled castes or Dalits)]

He also observed that the curriculum, quality, and dedication of teachers, as well as the teaching methodologies were far superior to those of their current European counterparts.

In his final report, Sir Thomas Munro concluded,

“The state of education here exhibited, low as it is compared with that of our own country, is higher than it was in most European countries at no very distant period.”[3]

2. A. D. Campbell’s Report – Bellary – 1822-23 [6]6

Another official report, prepared by A.D. Campbell, the Collector of Bellary, is well-known for its extensive and detailed information on the status of Indian indigenous schools in the early 18th century.

As per his report, in the district of Bellary, there were 533 schools with a student population of 6,338. The caste-wise distribution of the students (males) was as follows:

• Brahmin: 1,187 (18.6%)

• Vaishya: 982 (15.3%)

• Shudra: 3,024 (47.3%)

• Other castes: 1,205 (18.8%)

The figures showed that the so-called lower castes comprised almost 66% of the school population. This data emphatically debunks the claim that indigenous, native schools were inaccessible to the lower strata of the society. On the contrary, it proves that in the 18th and 19th centuries, there was no caste barrier, at least in the field of education.

Type of Education Imparted in Indigenous Schools [3,4]

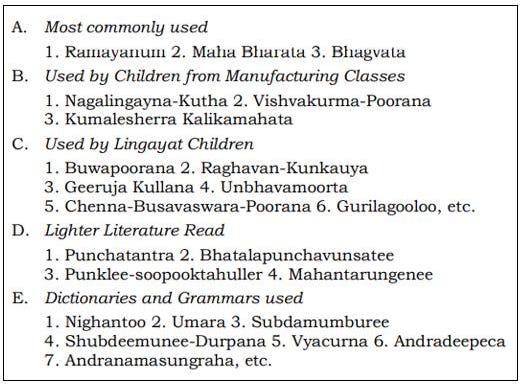

The various surveys conducted across the Madras presidency also included detailed information on the type of education provided in the schools (subjects, books, school timings, duration of education, etc.).

The students in most of the indigenous schools were taught reading, writing, and arithmetic. Following is the list of books used in the schools:

Bellary

Bellary was associated with the Kishkinda Kingdom of Ramayana times. Hampi, the capital of Vijayanagara Kingdom of Krishnadevaraya was also located in this Bellary area

Rajahmundry

In the institutes of higher learning, subjects like theology, law, astronomy, metaphysics, ethics, poetry, literature, medical science, music, and dance were taught. A lot of these subjects were also taught privately by various scholars.

While Brahmins mostly preferred subjects like Theology, Metaphysics, Ethics, and Law, subjects like Astronomy and Medicine were studied by students from varied castes. Curiously, among all castes, barbers were considered the best in Surgery.

Another observation made by various district collectors was that it was considered the duty of Brahmins to receive and impart knowledge of religious scriptures (i.e., Vedas, Puranas, and Shastras).

It was estimated that the number of students receiving "private" education was several times the number of those who were receiving institutional education. In Madras, the number of private students was estimated to be 4.73 times higher than those studying in native schools. Among the privately tutored students, Brahmins and Vaishyas constituted 58%, while Shudras and other castes constituted 28.7% and 13%, respectively.

3. William Adam Report – Bengal Presidency – 1836-38 [7]7

In 1835, the Governor-General of India, Lord William Bentinck, commissioned a Christian missionary, William Adam, to conduct research on the state of indigenous education in the Bengal presidency (area of Bengal and Bihar). Adam conducted three surveys and published his final report in 1838.

In his first report, Adam stated that in the 1830s, there were about 1,00,000 village schools in Bengal and Bihar. This statement, although not taken from official records, was based on observations made by various British officials and data from previous surveys (note that Thomas Munro, in his survey, also stated that "every village had a school"). Similar statements were made by officials like G.L. Prendergast (Presidency of Bombay, 1820) and Dr. G.W. Leitner (Punjab, 1882). Adam also observed that, on average, there were around 100 higher learning institutions in each district of Bengal.

Adam’s second report covered Nattore Thana in the Rajshahy. Findings from this report revealed that elementary school education was imparted between ages 8 and 14. Also, education in schools of learning was imparted between ages 11 and 27. The 485 villages had 123 native general medical practitioners, 205 village doctors, 21 (mostly Brahmin) smallpox inoculators, and 60,297 midwives.

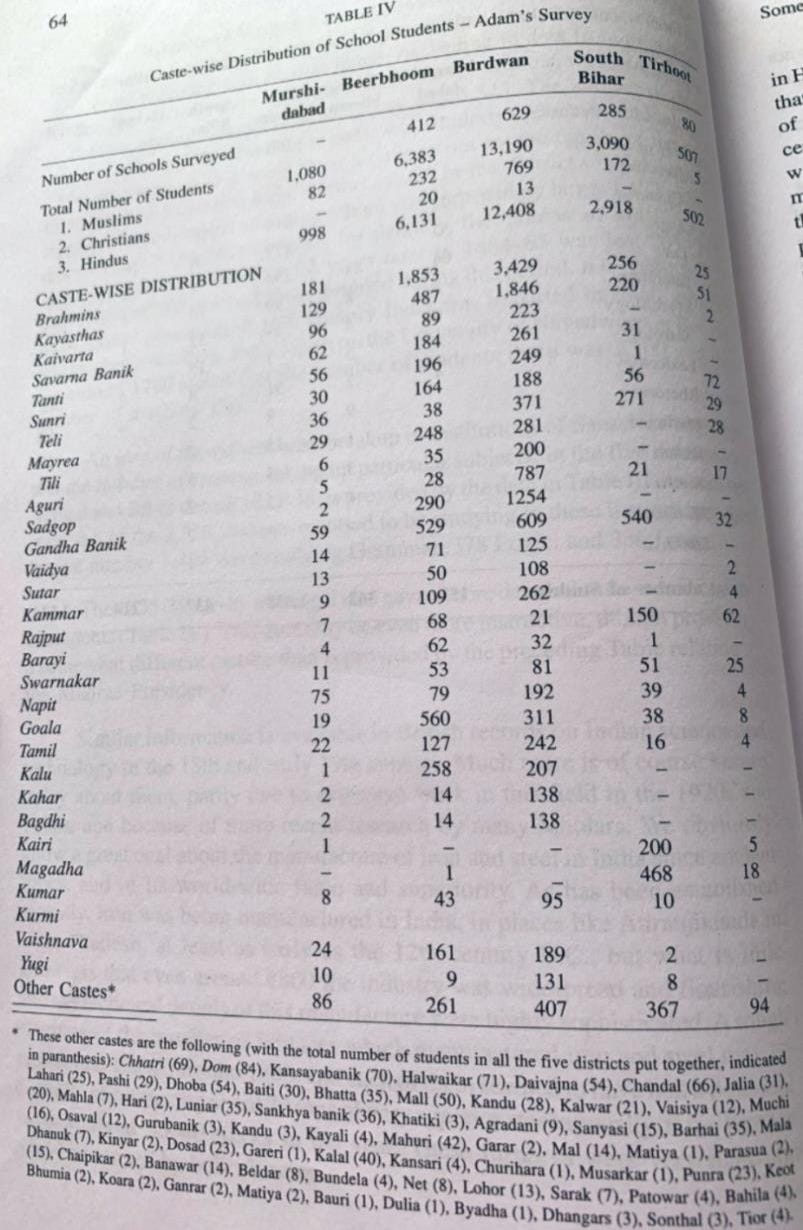

Adam’s third report was the most extensive among all three reports. It revealed some eye-opening information on the caste distribution of both students and teachers.

Caste-wise distribution of school students in Bengal Presidency [Adam’s report, 1838] *Other castes included castes considered lower than Shudras (current-day scheduled castes or Dalits

Caste-division of Students

In Bengal, Brahmins and Kayasthas together comprised less than 40% of the total students. However, in Bihar, they comprised only 15–16%. In both state districts, most of the school students belonged to the so-called lower castes.

Data from the Burdwan district also revealed a surprising fact: There were 61 Dom and 61 Chandal school students (Dalit castes), which was almost equivalent to the number of Vaidya students (126).

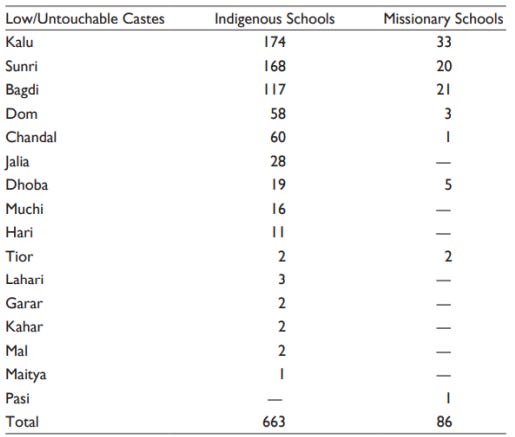

Dalit caste students in schools in Bengal [Adam’s report, 1838]

Another interesting finding was that a lesser number of lower caste students were enrolled in missionary schools vs. indigenous gurukuls. For example, in Burdwan’s 13 missionary schools, there were only 86 students from the Dalit castes (4 scholars from the Dom and Chandal castes). On the other hand, 674 scholars from these same castes were studying in the “native (indigenous) schools”.

Caste-division of Teachers

The teachers, similar to the students, came from various caste and religious groups. There were Hindu, Muslim, and Christian teachers, from more than 30+ caste groups. The major proportion of teachers were Kayasthas, Brahmins, Sadgops (Yadav caste), and Aguris (an agricultural caste). However, there was a sizeable number of teachers from other castes as well (including Chandal, Dhobi, Tanti, Kaivarta, etc.). Note that there were teachers from Dalit castes as well (e.g., there were 6 teachers from Chandal caste).

In his report, Adam mentioned- "Parents of good caste do not hesitate to send their children to schools conducted by teachers of an inferior caste and even of a different religion”. Subjects taught in Indigenous Schools

The key subjects taught in these native schools/learning institutions included Grammar, Accounts, Logic, Law, Literature, Mythology, Astrology, Lexicology, Rhetoric, Medicine,

Vedanta, Tantra, Mimansa, and Sankhya. There were also many institutions teaching Arabic and Persian.

4. Survey by T. B Jervis - Bombay Presidency - 1824-25 [8]8

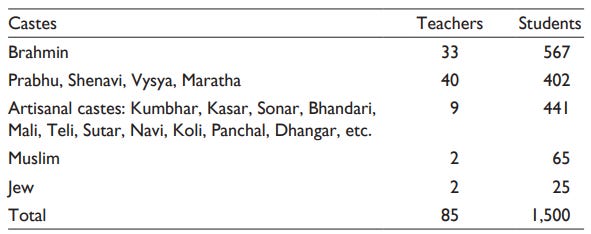

Data from the survey conducted in the Bombay presidency showed that there was a mix of castes, both among teachers and students. In the Ratnagiri district, the majority of the school students belonged to the artisanal castes. Almost 60% of teachers were non-Brahmins9.

Castes of Teachers and Students in Ratnagiri District [9]

[From a letter of T. B. Jervis to the secretary to the government, 1824]

Collapse of Indigenous Education due to British colonial rule

Various official and unofficial reports from the 18th-19th century period indicate that it was the British colonial education policy that propagated and solidified the caste divisions and discriminatory practices in the education system. The key amongst these reports is the survey by Dr. G.W Leitner, which was explicitly critical of the British policies.

G.W Leitner Survey and Feedback – Punjab – 1882 [10]10

Dr. G. W. Leitner was the Principal of Lahore Government College and also served as an acting Director of Public Instruction in the Panjab. He conducted an extensive survey of indigenous education status in Punjab in 1882. In addition, he also did a comparative analysis with the data available from previous surveys (Munro, Adam, and 1850s data). Leitner claimed that the British rule, instead of advancing, had led to a decline in the field of indigenous education. His findings showed that the number of students receiving education had dropped by almost 50% from Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s empire to British colonization. He held the British authorities responsible for the decay, and destruction of the indigenous education in the Punjab.

In his book on the ‘History of Indigenous Education in the Punjab, he wrote –

“I am about to relate-I hope without extenuation or malice-the history of the contact of a form of European, with one of the Asiatic, civilizations; how despite the best intentions, the most public-spirited officers, and a generous government that had the benefit of the traditions of other provinces, the true education of Punjab was crippled, checked and is nearly destroyed; how opportunities for its healthy revival and development were either neglected or perverted; and how, far beyond the blame attaching to individuals, our system stands convicted of worse than official failure.”

How was Caste Discrimination Propagated by the British? [9]

Early educational institutions established by the British between 1790 and 1820, provided educational access to only Brahmins (e.g., Sanskrit colleges of Calcutta, Banaras, and Poona). Similarly, many British government officials and educationists formulated policies that inhibited/restricted educational access to lower-caste students.

British members of Bengal’s General Committee of Public Instruction (established in 1823), argued that its aim should be to educate “respectable individuals, of whom its members will consist of men, who by their Brahmanical birth, as well as by their learning, exercise a powerful influence on the minds of every order of the community.” [11]11 H. T. Prinsep, a member of this committee adamantly refused to allow the Calcutta Madrassa to teach English to “a very inferior class of scholars, particularly sons of domestic servants.” [12]12

M. Elphinstone, the Lieutenant-Governor of Bombay, insisted on recruiting only Brahmins as teachers. [13]13 Colleges were instructed to impart education to only “students from respectable backgrounds”. [14]14 Even government employment was restricted to “respectable Mahommedans and Brahmins alone”. [15]15

The early schools and colleges that had an intermixing of upper-lower caste students were closed down citing “dearth of efficient masters and lack of resources.” [16]16 The overall aim of the British Board of Education was to confine education to natives of good caste and superior classes.

Conclusion

Over the years, we have been led to believe that the Indian indigenous education system was discriminatory in nature and was accessible only to upper castes, especially Brahmins. Another misconception is that the indigenous educational system was primitive and lacked any advanced, technical education. In fact, it is believed that the British brought the advancement of the education system in India and promoted caste equality in the fields of education.

However, the memoirs from various foreign scholars, as well as British-commissioned reports from the early 18th century bust all these misconceptions. Historical data clearly shows that Indian indigenous education was, in many ways, superior to contemporary European education. Data also reveals that caste or religion was not a barrier to education and students from all castes were getting educated together. The school population in these indigenous schools was dominated by lower caste students (Shudras). Children from the so-called Dalit castes were also getting educated (although these numbers were fewer, compared to other castes). It may be noted, however, that not all castes enjoyed free access to all levels of educational disciplines. Religious studies were more or less restricted to Brahmins while vernacular studies, (technical studies, literature, medicine, mathematics, etc.) were open to all castes.

As the British gained control over the government and educational resources, they monetized the entire educational system. They also devoted all their energy (rather intentionally) to developing only Western education, with a singular focus on higher and secondary schools. As a result, due to a lack of financial aid or government support, the native educational system collapsed with time. The historical records also indicate that it was the British colonial rule which strengthened the caste system and led to discriminatory practices, within the field of modern education. While British liberals may have supported the education of Shudras and Dalits, the colonial state policies prevented any equality and institutionalized caste prejudices and discrimination.

Data shows that the indigenous educational system enabled people from all social strata, leading to a cohesive socio-cultural environment. However, this calculated phasing out of the indigenous education system by the British and substituting it with an unfamiliar, non-native educational system, led to long-term adverse consequences for India. The literacy rate dropped, educational flow to the lower strata of society was restricted and the caste- discrimination solidified with time. This system also led to a great deterioration in the socio-economic conditions, leading to a fractured society.

For long, it has been believed that it was the Hindu religious system, which has led to a hierarchical and discriminatory educational practice. This misconception has not only led to prolonged angst amongst the lower castes but also has led to a disintegration of social cohesiveness. However, the historical evidence not only challenges the current assumptions about pre-British indigenous education but also questions the role of British educational policies. With all these facts, it’s time to re-analyze the currently held political and academic beliefs to prevent any further socio-cultural disintegration of Indian society.

REFERENCES

Parulekar RV. Survey of Indigenous Education in the Province of Bombay, 1820-1830. Asia Publication House. Bombay. 1951

Nurullah S and Naik JP. History of Education in India during the British period. Bombay. 1943

Hartog PJ. Some Aspects of Indian Education Past and Present, OUP. 1939

Dharampal. Indian Science and Technology in the Eighteenth Century: Some Contemporary European Accounts. Other India Press. Goa. 2000

Dharampal G. Essential Writings of Dharampal. Publications Division, Government of India. 2015

Rao PV. Myth and Reality in the History of Indian Education. 2019

Decay of Village Community and the Decline of Village Schools of Vernacular Education in Bihar and Bengal in the Colonial Era: A Sociological Review [Revised version of the paper entitled “Decline of Civil Society in India in the Colonial Era: The Case of Indigenous Village Schools of Vernacular Education”, presented at the conference on “Social Consciousness and culture in Modern India” sponsored by Centre for Studies in Civilizations, India International Centre, New Delhi, 27-28 February 2006]

Footnotes:

Dharmapal. The Beautiful Tree: The Indigenous Education in the Eighteenth Century. New Delhi. 1983 [Introduction]

Ibid [Preface], pp 1-6

Ibid [Minute of Governor Sir Thomas Munro ordering the collection of detailed information on Indigenous education (TNSA: Revenue Consultations: Vol.920: dated 2.7.1822), Annexure I]

Ibid [Findings from District collectors (Madras presidency) to Board of Revenue, Annexure II-XXIX]

Ibid [Minute of Sir Thomas Munro, Mar 10, 1826 (Fort St. George, Revenue Consultations), Annexure XXX]

Ibid [Collector, Bellary to Board of Revenue, Sep 17, 1823, Annexure XIX)

Adam W. (ed by A. Basu). Reports on the State of Education in Bengal 1835 and 1838. Calcutta. 1941

Rao PV. Colonial State as ‘New Manu’? Explorations in Education Policies about Dalit and Low Caste Education in Nineteenth-Century India. 2019

Ibid [letter from T. B. Jervis to the secretary to the government, Sep 8, 1824, General Department 63 of 1824], pp 88

Leitner GW. History of Indigenous Education in the Punjab since Annexation, and in 1882, 1883. Punjab, Patiala. 1973

Sharp H. Selections from the educational records, part I 1780–1839. Superintendent of Government Printing. Calcutta. 1920

Parliamentary Papers (1852–1853). London: House of Commons.

Education Consultations (1825–1826). Mumbai: Maharashtra State Archives

Public Consultations (1836–1852). Chennai: Tamil Nadu State Archives

Appendix to Report from the Select Committee of the House of Commons (1832). London: J.L. Cox and Sons

Richey JA. (1921). Selections from the educational records part II 1840–1859. Superintendent of Government Printing. Calcutta. 1920

Where is Part 2?